Clockmakers’ Company Cataloguing Project

We are pleased to announce that last year saw the long-awaited completion of cataloguing of the most recently deposited records of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers, as well as re-cataloguing of some of its past deposits.

The Clockmakers’ Company – still very much active, with members ranging from clockmakers and watchmakers to collectors, auctioneers, horology historians and other enthusiasts from around the globe – traces its history back to 22 August 1631, when King Charles I finally granted the charter to establish a separate, specialist company for horological crafts. Before then, most English clockmakers were members of the Blacksmiths' Company, since many were involved in the production of large clocks for towers and churches. Some also joined companies that were not related to the clockmaking craft.

By 1631, the establishment of a company dedicated entirely to the clockmaking craft had become something of a necessity. Whereas smaller clocks and watches were either imported or produced by immigrant craftsmen during the reigns of King Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I – who encouraged foreign craftsmen to settle in England - the local production of clocks and watches began to prosper during the reign of King James I. The first Master of the new Clockmakers' Company was David Ramsay, former Chief Clockmaker to King James I and the creator of the iconic star-shaped 'Nativity' watch which is one of the highlights of the Company's museum collection.

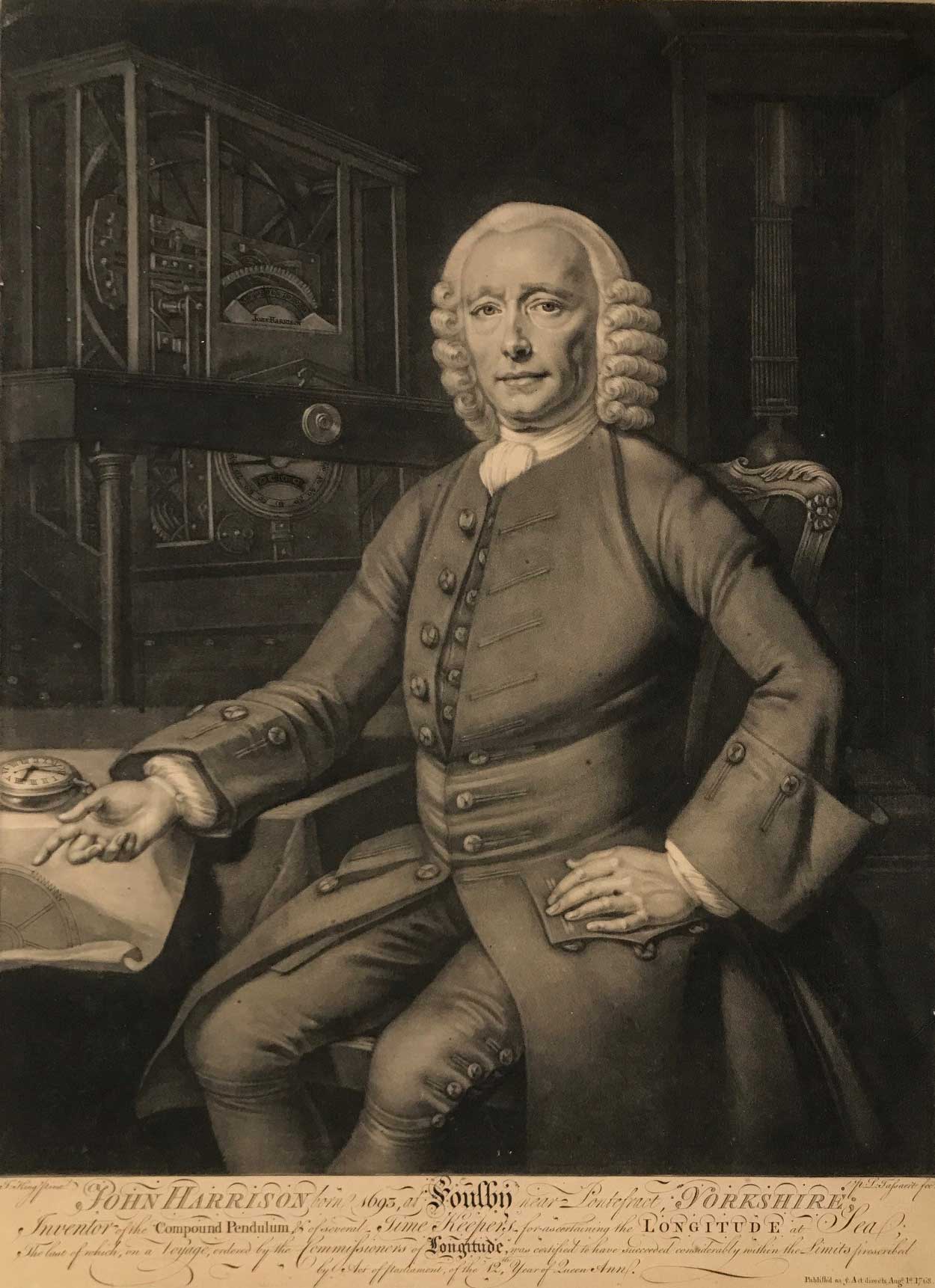

London's clock and watchmaking started gaining an international reputation for excellence from 1660 onwards, when the restoration of the monarchy and technological advances - such as the balance spring and jewel bearing - allowed it to flourish even further, ushering in the trade's Golden Age. Its most celebrated achievement was the development of the marine chronometer by John Harrison in 1735, which solved the problem of calculating longitude at sea and won him and his son William the coveted Board of Longitude prize. Although Harrison, a Yorkshireman, was never a member of the Clockmakers' Company, he was assisted by the Company members - such as George Graham - both financially and professionally. Their papers, which include drawings, letters and petitions are among the records deposited by the Company at LMA.

The Clockmakers’ Company records, including its ordinances, go right back to its foundation. Their survival is remarkable considering that the Company never owned a hall, meeting in taverns or on other companies' premises. Its documents and treasures were kept in the great chest, which resided in the Master's home and was moved every year; as it turned out, a fortunate habit which allowed the chest and its contents to survive the Great Fire of 1666. Despite the lack of its own premises, the Company had periods of stability when renting rooms, sometimes for decades at a time, from grand hotels to smaller venues such as the King’s Head Tavern in Poultry. This made it possible for the Company to establish its own collection of horological books at the instigation of F.J. Barraud, a watchmaker from an illustrious clockmaking family. A Library Committee, with members including Barraud and J.T. and B.L. Vulliamy, was established in 1813. This led to the creation of one of the most comprehensive and unique horological libraries, with many rare works and books annotated by their authors and donors; this library is now housed at the Guildhall Library. At the same time, purchases of rare watches by the Company members resulted in the establishment of the Clockmakers’ Collection, now the oldest surviving collection of clocks and watches in the world. Beautifully curated and telling the history of the clockmaking craft through the stories of people who were involved in it through the centuries, it can be admired at the Science Museum in Kensington, where it has been based since 2015. Among the records catalogued and made available to the public as a result of the recent project is a series of clockmakers’ portraits (reference CLC/L/CD/I), which allows us to put faces to some of the renowned craft members.

In addition to keeping its own records and developing a library and museum collection, Clockmakers’ Company has long acted as the depositor for records of London-based horology-related organisations, families, businesses and individuals. The Company’s own and related collections have been steadily arriving at the Guildhall Library Manuscripts Section (now part of the LMA) since 1950. As of 2023, 46 separate deposits have been made, and more are expected to arrive in the future. These include 30 related collections, some of which had been catalogued in the past, somewhat confusingly, as part of the Company’s own archive. One of the aims of the recent project – in addition to cataloguing most recent acquisitions - was to separate such records from the main collection and assign unique reference numbers to them.

The John and William Harrison archive is the best example of this: it now forms a separate, properly arranged collection under reference number LMA/4807, which makes it both more prominent and more suited for expansion should more records be added to it in the future. In fact, new records were added to the Harrison collection very recently. Not related to John Harrison’s horological pursuits, they document his interest in music and music theory and give us a glimpse of his stint as a choirmaster in Barrow.

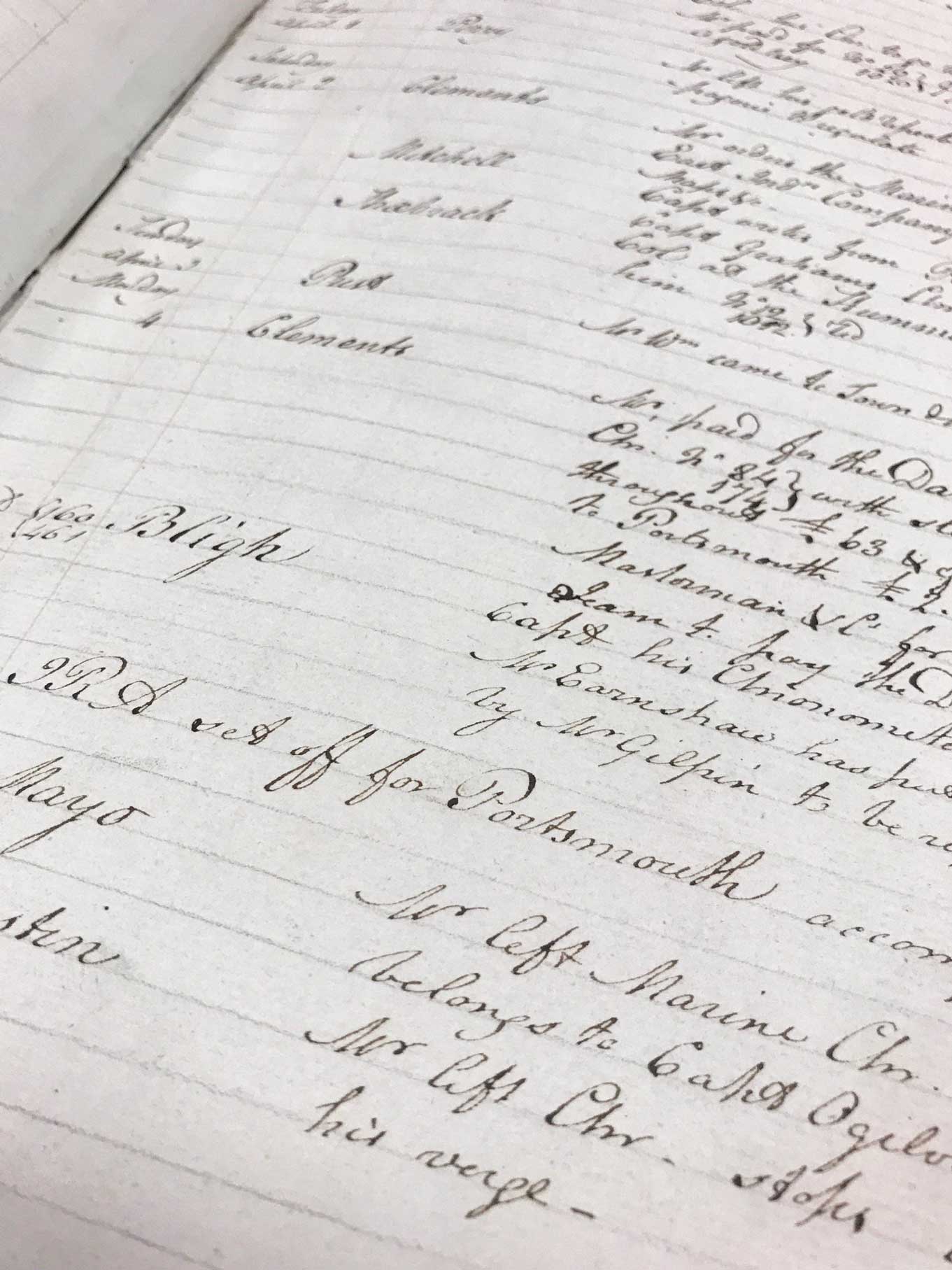

Among other highlights of the recently catalogued records is the Arnold daybook. John Arnold (d. 1799) and his son John Roger (d. 1843) were celebrated watch and chronometer makers, with John Roger serving as the master of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1816. The hefty daybook, ranging from 1796 to 1830, is a unique record of their watch and chronometer making business, including customers’ names, as well as everyday management affairs of their Chigwell estate. This is quite probably the only volume in existence in which the manufacture of a marine chronometer for Captain Bligh (of the mutiny of the Bounty fame) is mentioned alongside Betty the heifer giving birth to a ‘cow calf’! The volume (ref LMA/4804/02/001) is now awaiting digitization, as it is likely to attract quite a lot of attention from researchers.

However, one of the most remarkable recent additions to the clockmaking archives must be the Vulliamy watchmaking books, as their survival is a story in itself. The Vulliamys, originally from Switzerland, were among the most renowned clockmakers and watchmakers in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain. Justin Vulliamy moved to Britain in the 1730s and set up partnership with his father-in-law Benjamin Gray who was appointed watchmaker to King George II in 1742. Upon Gray’s death, the Vuillamy family retained the royal warrant for three generations. As we have seen, members of the family were also instrumental in establishing the Clockmakers’ Library and Collection. Due to the Vulliamys’ royal links, some of their records, including some workbooks, are kept at The National Archives.

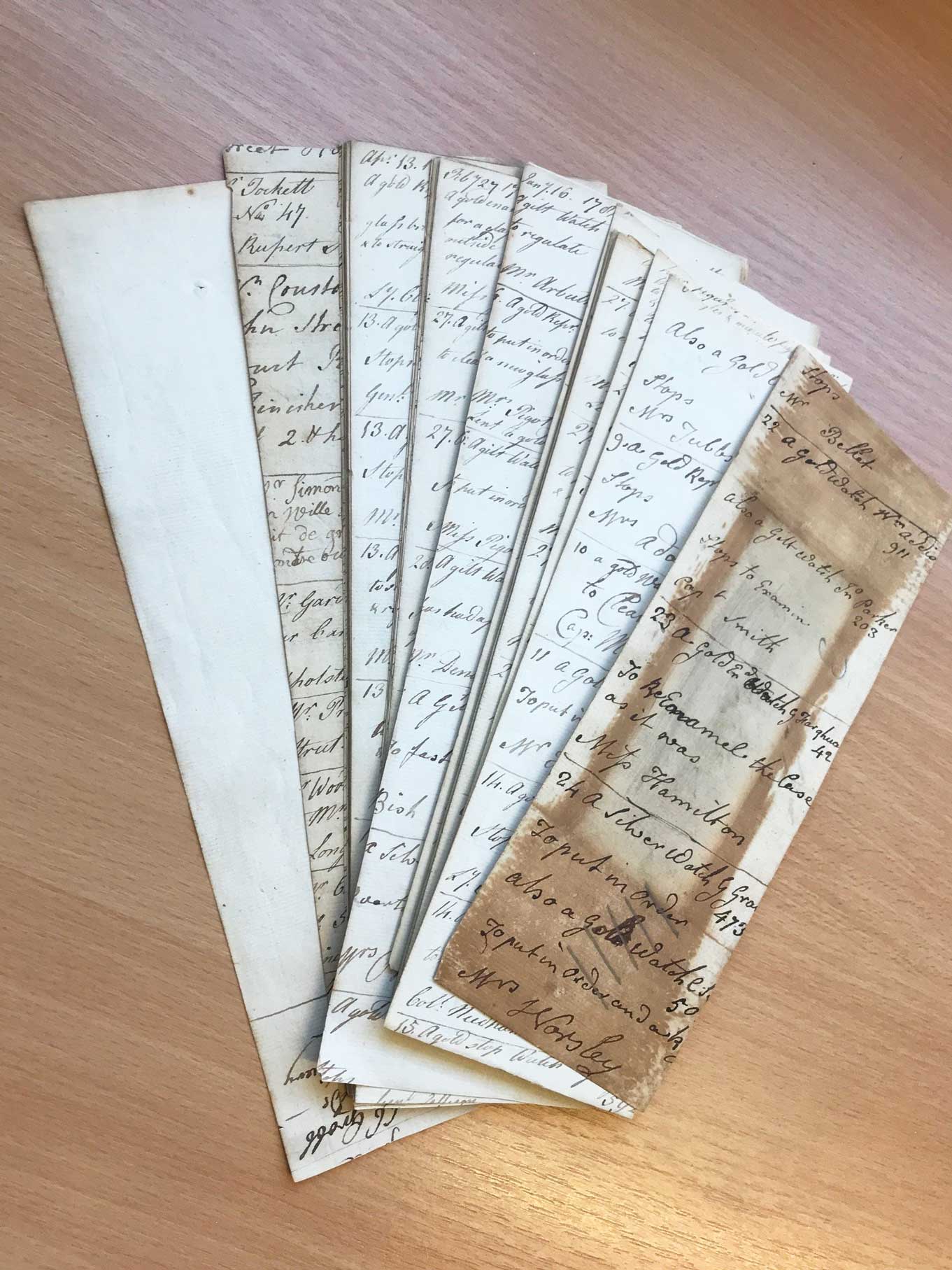

In 2003, the Clockmakers’ Company received a message from the Royal Collection Trust, saying that several bunches of cut-up records had been found as padding in one of the royal carriages. These turned out to be 272 heavily trimmed and cut-up fragments from Justin Vulliamy's watch day books, starting in the 1750s when he was still in partnership with Benjamin Gray, and finishing in the 1780s, when he was working with his son, also Benjamin. Although the edges and tops of most of the sheets have been cut off, together with dates in most cases, the details of watch commissions and repairs, watchmakers' names and watch numbers, as well as names of the customers, ranging from the royals to commoners, have been preserved. The Trust gifted the records to the Clockmakers’ Company, but that was not the end of the story. Nine years later, in 2012, another message came from the Trust, this time about similar bundles of records found during the conservation of Chinese vases at Marlborough House, in one of the vase’s mounts. Sure enough, they came from the same volumes as the previous set. The fragments have been photographed by the Company and have now been meticulously catalogued page by page in the order they were received (reference LMA/4813/02). They were individually packaged in archival-grade polyester sleeves to ensure their safe handling, so they can be consulted by researchers. However, restoring them to their original page order would require a separate research project.

Other recently catalogued collections included in the Clockmakers’ project are the business records and workbooks of Usher and Cole (LMA/4812), Rowley and Parkes (LMA/4810), additional records of Charles Frodsham and Company (CLC/B/043), the research papers of clockmaking historian Dr Vaudrey Mercer (LMA/4809), and an autograph letter of Nevil Maskelyne, Astronomer Royal (LMA/4808).

The Clockmakers’ Company is still actively involved in supporting, promoting and preserving horological crafts and industries, which in 2019 were added to the Heritage Crafts Association's Red List of Endangered Crafts. It does so through grants, prizes, mentoring, networking, library, online activities, the Clockmakers' Museum, and not least through making its remarkable archive available to the public. The Company’s own records can be found on the LMA catalogue under reference CLC/L/CD, where related collections with their individual reference numbers are also listed. Most records are available for consultation at the Guildhall Library, although some require the Company’s permission, and some are available only in a digital or microfilm form for preservation purposes. As the Company keeps expanding its record holdings through donations and purchases, not least through their benefactors’ generosity, they will continue to be an ever-growing goldmine of horological knowledge.

For anyone interested in the Company’s history, The Clockmakers of London (2nd edition, 2018), a book by the Company’s Part Master Sir George White, which has been used in the writing of this article, is an excellent starting point. More information about the Company’s current activities can be obtained from their website The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.