Colney Hatch Mental Hospital

Exploring Colney Hatch Mental Hospital archives at LMA: finding the patient’s voice

Delving into hospital archives tends to reveal much of the top-down workings of the institution, but little evidence of the voice of patients who received care, and their families who supported them. Since the raison d’ȇtre for a hospital is to treat ill, injured and traumatised people, and enable them to live their lives as well as possible, a historical understanding of how patients experienced care is important. Claire Hilton, Historian in Residence at the Royal College of Psychiatrists and Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London has been researching the archives of Colney Hatch Mental Hospital (CHMH) for the period 1919-1930. In this article Claire aims to shed some light on the experiences of its patients through letters she has found in those archives.

Introduction

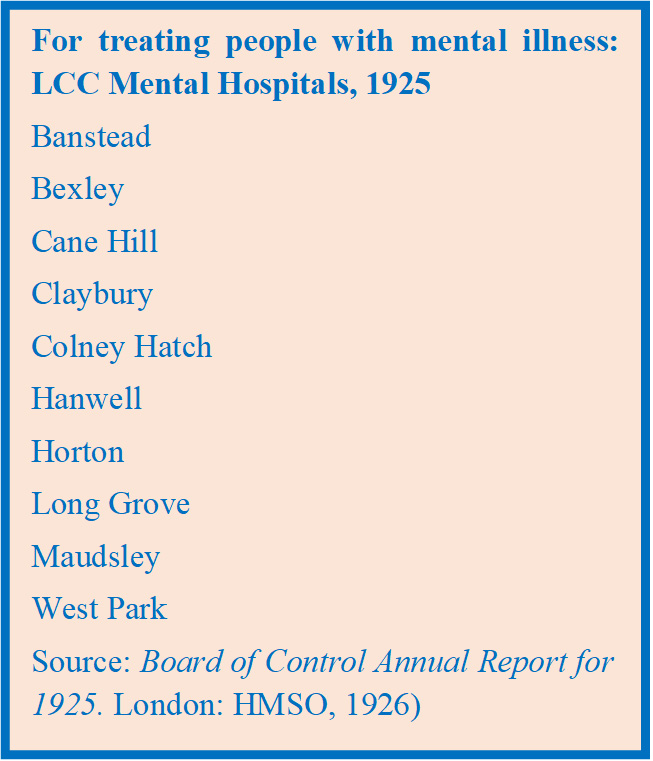

Colney Hatch was a large, public mental hospital with about 2,000 beds under the auspices of the London County Council (LCC). It, and the other LCC mental hospitals (see table, source the Wellcome Collection), served the metropolis’s population.

Mental hospitals of past times have often been portrayed adversely. Sometimes staff were unkind or even cruel to patients, and some scandals reached the headlines. In contrast, humane care rarely attracted public attention. Likewise, cruelty in hospitals and care homes today hits the headlines, with good practices taken for granted. The occurrence of scandals of care does not mean that the whole staff were, or are, unkind; good and bad practice can coexist in the same institution at the same time.

Delving into hospital archives tends to reveal much of the top-down workings of the institution, but little evidence of the voice of patients who received care, and their families who supported them. Since the raison d’ȇtre for a hospital is to treat ill, injured and traumatised people, and enable them to live their lives as well as possible, a historical understanding how patients experienced care is important. This article aims to shed some light on this.

Some of the records I have consulted are currently closed under data protection rules to maintain the confidentiality of individuals who may be alive today. I am grateful to LMA for allowing me to access them through their scheme for academic researchers. This required me to sign an undertaking to maintain confidentiality. The examples I use are therefore anonymised.

Listening to patients

In archive collections, accounts about how institutions provided for and treated their patients readily appear in committee minutes, formal reports and other official documentation. These may record patients’ good and bad experiences, but only as interpreted through officialdom. In the mental hospitals, if patients complained they were often not believed, their negative reports being attributed to their mental illnesses causing them to misinterpret happenings. In contrast, their compliments were accepted and deemed to be markers of good, or improving, mental health. (Today we understand that, despite suffering from even severe forms of mental illness, people can give all sorts of opinions with accuracy.) Officials regularly discounted patients’ views in favour of those of staff, with evidence from the witness holding the highest rank often carrying the most weight, even though that person might also be a perpetrator. The officials caused a disservice to the patients by closing their eyes to the possibility that staff could be anything other than kind.

So, what evidence do we have about good and bad practice in the words of the patients? Sometimes letters from patients, and their friends and family on their behalf, can be found lurking among official records. Thus, in the series of LMA files ominously titled 'Reception orders, medical certificates, notices of death, discharge or removal and correspondence for female patients who died or were discharged or removed', appear some letters from patients and their close relatives. Unfortunately, for male patients at CHMH no parallel series appears to have survived.

I will give you some examples of the personal letters which indicate the experiences of patients and their families at CHMH.

Letters from Annie and Minnie

Annie was 41 years old when admitted to CHMH in 1911. She was discharged 17 years later. Below is a transcript of one of her letters to the hospital’s medical superintendent, Dr Gilfillan (Ref: H12/CH/B/47/038, folder 2). It was written after discharge. Letters written by patients at that stage were probably motivated by genuine feelings, rather than any pressure to show gratitude or to impress their recovery on the authorities to ensure their discharge. There are some gaps in this transcript due to words being obscured by the filing clerk using glue on the corners of the documents needing to be kept together.

'Dec 2nd 1928

Dear Sir

According to promise to let you know how I am getting on this is A very nice Old Place …

go for nice walks and shops to Purchase anything that people require if you have the money to pay for it

People have 9d a week here…

I am going to do my best to get on and as soon as I get A Situation

Kindly give my best respects to Mrs Lancaster with best of wishes to You Dear Sir.

Thanks for … Past Kindnesses

Believe me to remain yours Faithfully

Annie'

The hospital clerk replied encouragingly to Annie, on Dr Gilfillan’s behalf.

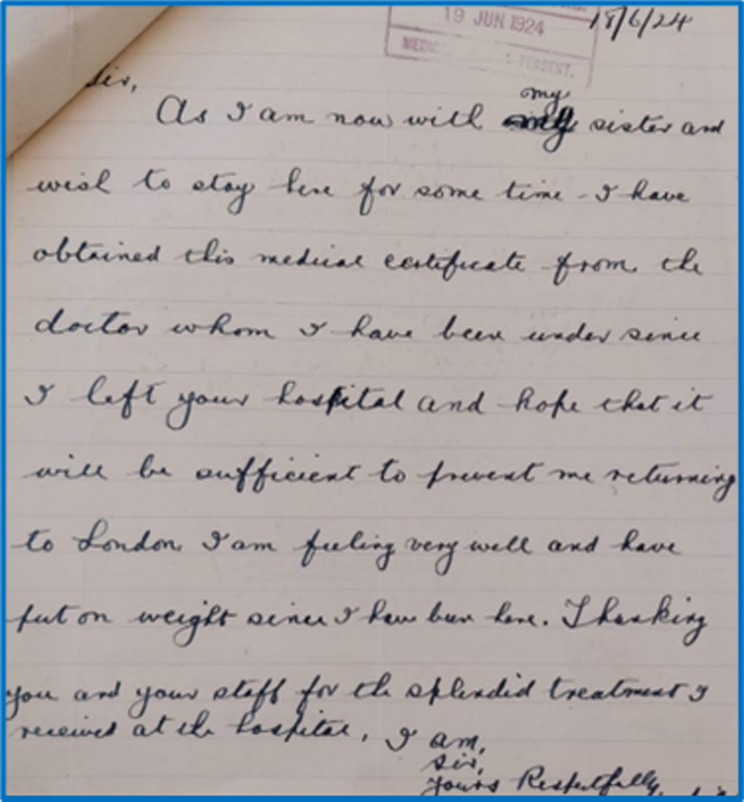

Another letter was from Minnie, a 24-year-old single housemaid, admitted in February 1924 in a 'strange', 'dazed' state. Three months later, she was sent on 'trial leave' to her sister who lived in Dorset. Minnie wrote to CHMH, grateful for her 'splendid treatment', and enclosing the medical certificate from a local general practitioner stating that she was well. (Ref: H12/CH/B/47/032, folder 3)

A letter from Leonie’s father

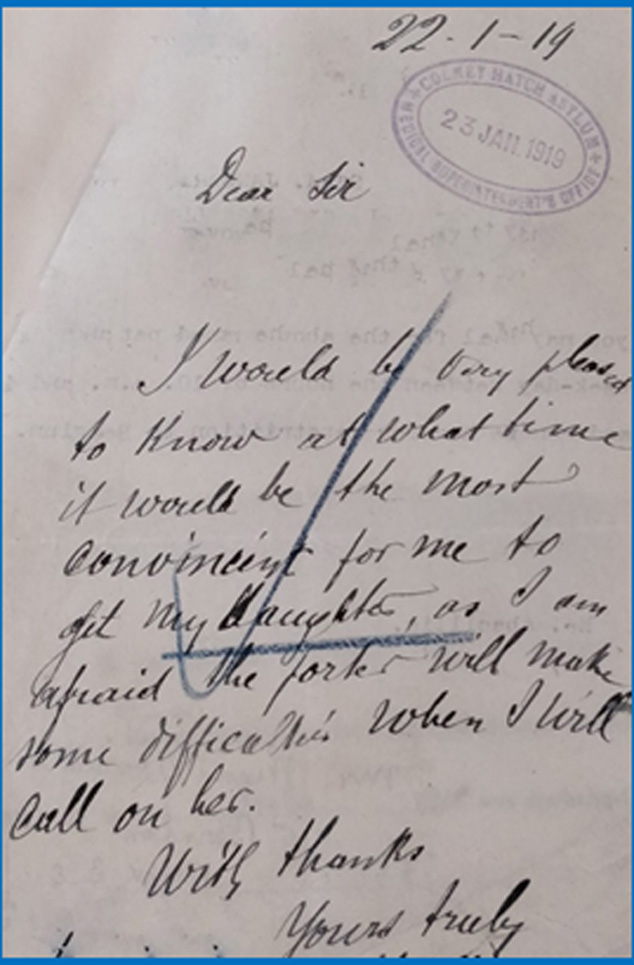

A third letter comes from the father of a patient, Leonie, in 1919. Leonie had fled from Belgium with her family when Germany invaded in 1914 at the beginning of the First World War. Leonie was 17 when she came to London. She found employment in a munitions factory. In 1918 she was depressed after giving birth and was admitted to CHMH. Soon after the war, her father arranged to take her back to Belgium, and wrote to the CHMH authorities (Ref: H12/CH/B/47/018):

'I would be very pleased to know at what time it would be convenient for me to get my daughter, as I am afraid the porter will make some difficulties when I will call on her.'

The tick indicates that a reply was sent.

The father’s concerns probably reflected his previous experience of entering the hospital under the porter’s watchful eye. The letter may also resonate with public experience today, of how to get past reception in primary or secondary healthcare, by phone, online, or face-to-face, in a large, bureaucratic healthcare system.

Conclusions

I have deliberately chosen these letters to counteract popular stereotypes of negativity surrounding the former large, public mental hospitals. These sorts of letter help dispel the view that the hospitals were inherently cruel; that patients admitted to them were detained indefinitely; and that families abandoned their kinsfolk to their fate due to fear and stigma of mental illness. Our letters indicate kindness, loyal families, and that patients could leave mental hospitals having recovered from their mental illness.