Court of Orphans

Research using the Probate Inventories of the Court of Orphans

When trying to learn more about the people of the early modern City of London, researchers commonly find themselves using the Repertories of the Court of Aldermen held at the London Metropolitan Archives, or the livery company records at Guildhall Library. These records tell us a lot about the way the City was governed, but also about the people who lived and worked there, and the trades they practised. However, an often-overlooked court that sat in the Guildhall - the Court of Orphans - whose records are also held in the LMA, can also reveal a lot about life in early modern London. Specifically, the probate inventories of the Court of Orphans can tell us about the lives of London’s citizens, their business ventures, and the role that women had in London’s urban economy.

By the mid-sixteenth century, the Court of Orphans was a busy and thriving institution, and it functioned to look after the orphans of citizens of the Square Mile. Whenever one of the City’s freemen - such as a draper, fishmonger, or goldsmith - died leaving any underage children, his estate had to be processed by the Court of Orphans, and his children’s guardianship was managed by the City’s aldermen.

‘Orphan’ in this period of the City’s history was defined as fatherless, not parentless, meaning that women feature prominently in the Court of Orphans’ records as widows, mothers, and guardians. The Court’s administrative process was incredibly complex and required guardians and orphans to visit the Guildhall multiple times over a period of many years. This administrative process created a large amount of paperwork, most of which is still held by the LMA today, including probate inventories, petitions, and financial records.

The administrative process of the Court of Orphans

- Death of a freeman with a child under the age of 21

- An inventory of his estate brought to the court of orphans

- His estate was then divided into thirds, between his widow, his orphan(s) and bequests in his will

- The executor of the estate could either (1)deposit the inheritance in the City's chamber, or (2) keep it under the security of a recognizance

- If deposited in the chamber, the guardian would recieve finding money (interest) used to care for the orphan(s)

- A recognizance had to be supported by sureties who were liable to pay if the executor defaulted, but allowed the executor use of the inheritance in return for paying the orphan(s) interest

- Upon reaching 21, any orphan(s) could claim their inheritance from the Court of the recognitor, at which point they were 'satisfied' and left the Court's jurisdiction

Probate Inventories

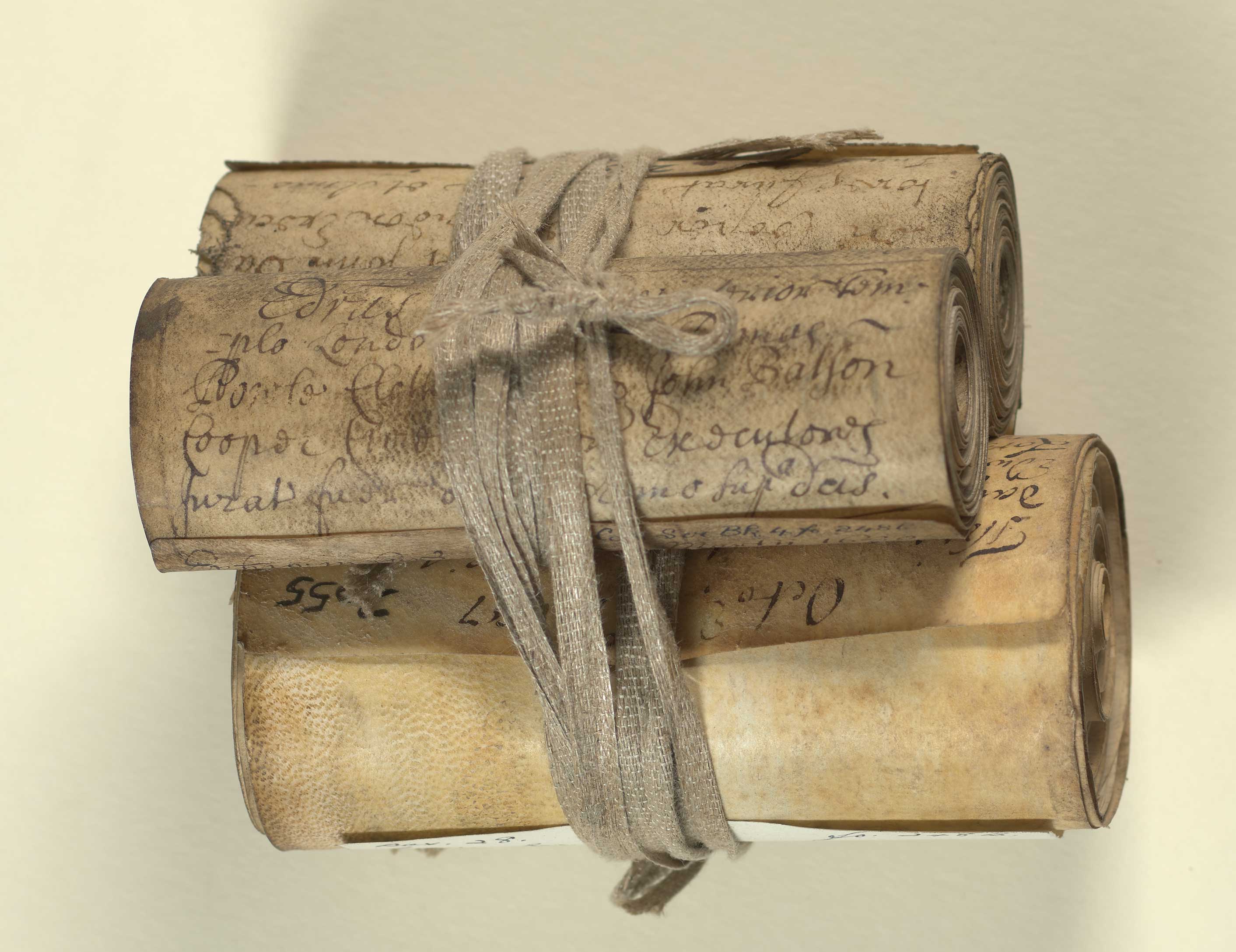

The probate inventories are by far the most popular record of the Court of Orphans, and they were drawn up shortly after a citizen died and then brought to the Guildhall for examination by the City’s common serjeant. They list everything a citizen owned at the time of their death, from furniture and clothing to crockery and money. The LMA holds over 3,300 probate inventories dating from 1660 to 1750 in the archive of the Court of Orphans, most of which record the estates of men, but a small number do relate to the estates of women. The inventories are made up of pieces of vellum that were sewn together and tightly rolled into bundles, with the name of the testator written in Latin on the reverse. While some are made up of one strip of vellum, some, like the probate rolls of Elizabeth Stevenson, are dozens of metres long.

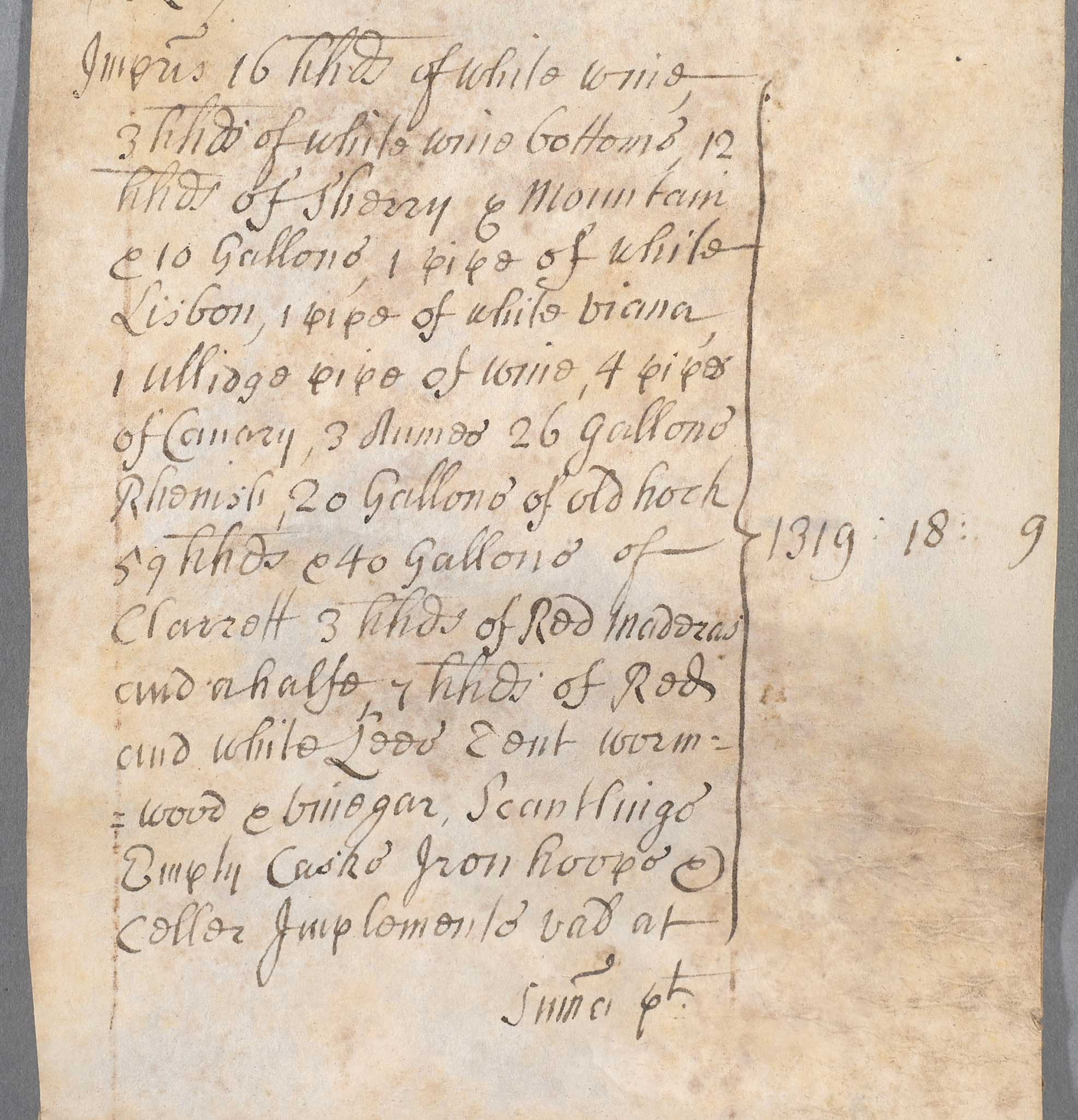

These probate inventories are incredibly rich and can be used by researchers to learn more about the items that people owned, the businesses they were running, and even the amount of debt they were in when they died. For example, the probate inventory of Prudence Wood (CLA/002/02/01/1631) from 1678 reveals that she lived on Lad Lane near the Guildhall, she ran a business working as a milliner - which in the early modern period was a person who sold ready-made items of clothing, rather than exclusively a hatmaker - and had over £6,000 owing to her in business debts when she died. Similarly, the probate inventory of the vintner Henry Kellett from 1711 provides rich detail of his public drinking house, Ship Tavern, on Threadneedle Street on what is now the site of the Bank of England. The tavern had several drinking rooms with 41 tables, two rooms at the top for the live-in ‘drawers’ who served the drinks, and over 50 gallons of wine and sherry in the tavern’s cellar, totalling over £1,300 in stock (CLA/002/02/01/2899).

The probate inventories also contain incidental, and sometimes sad information about people’s lives and misadventures. We know that the widow Anne Deacon died in or before 1675 after drowning in the Thames, as her inventory contains a payment of 10 shillings to a river waterman who ‘searched for [and] tooke up the body of the intestate’ (CLA/002/02/01/1049). Similarly, the tallow chandler Katherine Wilkinson had only recently taken on a new apprentice when she died in 1666, as the apprentice’s father petitioned to be reimbursed for the sum he paid for the apprenticeship (CLA/002/02/01/0644). The widow Grisell Reeve had previously run a failed carpentry business with her brother-in-law, as her inventory lists £530 debts that the pair racked up and were owing through the business. The Court of Orphans’ probate inventories remain some of the most detailed inventories to survive from the period, and they provide a rare insight into the everyday lives of working early modern Londoners.

More information on the Court of Orphans is available in the ‘Civic Courts of the City of London’ research guide on the LMA Collections Catalogue. Most of the probate inventories have corresponding entries in the common serjeant’s books (CLA/002/01). 25 probate inventories have previously been transcribed by P.E. Jones, Deputy-Keeper of Records for the Corporation of London from 1945 (CLA/002/03/004).