LCC housing records

Housing: using the London County Council collections at London Metropolitan Archives

Who are these records of interest to?

The housing records of the London County Council (LCC) are a rich resource for researchers from numerous disciplines. They are particularly good for those researching local history, history of the built environment, construction and building technology, architectural and design history and town planning between 1889-1965. They are also a valuable source for public art, design in the public realm, sociology and social history.

As very little material relating to individual tenants survives, it isn’t feasible to use these records to trace individuals for the purposes of family history. However, you can use the records along with photographs to get an idea of life on one of the LCC housing estates.

Introduction

The LCC was a major developer in Greater London and the South-East, building small-scale social housing estates in the 1890s which grew in scale and ambition to include the redevelopments of whole districts of London and the expansion of towns outside London.

This intensive building programme was a response to the poor conditions of existing housing, the demand to provide 'homes fit for heroes' after the First World War and after 1945, the need to rebuild due to the destruction caused during the Blitz, which obliterated swathes of London’s housing stock. This article explores the history of the LCC’s Housing Department, and helps you undertake research into the archives. Research tips and a guide to further resources can be found at the end.

1889 - 1914

The 1890 Housing of the Working Classes Act encouraged local authorities to relieve crowding in inner cities by building new homes. By 1914, the Housing of the Working Classes branch of the LCC had built over 10,000 new homes for Londoners.

Many of these new homes were part of 'slum clearance' schemes to replace poor quality housing. These low-rise inner-city estates usually featured several four- or five-storey blocks, often with communal facilities like laundries and clubrooms located on the ground floor. The first estate of this kind to be completed was the Boundary Estate in Shoreditch, which was designed by the principal architect for the LCC, Owen Fleming, in the Arts and Crafts style, and officially opened in 1900.

Other estates built by the LCC in this model include the Churchway Estate (St Pancras), Herbrand Street Estate and Bourne Estate (Holborn), Duke’s Court Dwellings (Covent Garden), Millbank Estate (Pimlico), Webber Row and Borough Road Estate (Southwark), Briscoe Buildings (Brixton), and Hughes Field Estate (Greenwich). Similar estates were built to rehouse people displaced by the LCC’s construction projects, like the Rotherhithe Tunnel, which resulted in the Brightlingsea Buildings north of the river and the Swan Lane Estate to the south.

Inspired by the garden city movement of Ebenezer Howard and socialist philosophy of William Morris, the LCC also built new ‘cottage estates’ on the fringes of the County of London where there was more space to build. The best known of the LCC’s cottage estates was Totterdown Fields in Tooting, which was officially opened in 1911. Others include the White Hart Lane Estate (Tottenham), Norbury Estate (Croydon), and Old Oak Estate (Hammersmith).

1918 - 1939

The LCC continued to build inner-city and cottage estates after the First World War, but on a much larger scale. The ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’ campaign after the First World War and 1919 Housing Act (Addison’s Act) put pressure on local governments to build, and the LCC’s Labour leadership had an ambitious housing agenda. During this period the Architecture Department was led by chief architects G. Topham Forest and E. P. Wheeler.

The first estate to be finished after the war was Tabard Gardens (Southwark) in 1925 which was a test bed for new ideas like higher buildings. It was the first LCC estate to have an electric passenger lift. Other inner-city estates built during this period included the White City Estate, Holland Estate (Spitalfields), Collingwood Estate (Bethnal Green), Whitmore Estate (Hoxton), Shore Estate (Hackney), Coventry Cross and Bow Bridge Estate (Bow) among many others.

These estates were often built to a standard plan - the five-storey red brick ‘walk up’ - with some individual flourishes. The Ossulston Estate (St Pancras) and Oaklands Estate (Clapham) are notable examples of the growing influence of European and art deco styles.

Helped by extensions to the transport network, the LCC also expanded its cottage estate housing beyond its own area (ie outside of the County of London). Becontree Estate in Barking and Dagenham was the largest out-county cottage estate built during this period, providing 25,000 new homes to over 100,000 residents. Completed in 1925, at the time it was the largest council housing development in the world. Becontree’s residents primarily came from the East End of London and comprised working class families with secure employment. For many new tenants, this was the first time they had lived in a house with a garden and an indoor toilet. Prospective tenants were vetted by the LCC, assessed for their suitability, family size and their financial situation. Although LMA’s holdings relating to tenants are limited, surviving tenants’ handbooks give an idea of the expectations placed upon new tenants (LCC/HSG/GEN/03/011).

Other cottage estates built during this period include Saint Helier (Merton and Sutton), the Downham and Bellingham Estates (Lewisham), Castlenau Estate (Barnes), Dover House (Roehampton), Wormholt Estate (Hammersmith), Watling Estate (Edgeware), Mottingham (Bromley) and Friday Hill Estate (Chingford).

The unprecedented scale of these estates meant that the LCC needed to build facilities for all aspects of residents’ lives, from shops to pubs, schools, community associations, gardens and churches.

1945 - 1965

The devastation wreaked on London during the Second World War necessitated rebuilding on a vast scale. Plans for reconstructing the capital were laid out by town planner Patrick Abercrombie and the architect to the LCC, John Henry Forshaw, in their 1943 County of London Plan. Abercrombie and Forshaw championed the idea of ‘mixed developments’, where different types of housing were combined with schools, community centres, libraries, homes for elderly people, health clinics and shops to create a ‘neighbourhood unit’. Although the LCC continued to build cottage estates and blocks in the interwar style (like the Honor Oak Estate, Lewisham, and the Hilldrop Estate, Islington), most new estates followed the principles of mixed development: pioneered at the Woodberry Down Estate (Hackney) and the more adventurous Lansbury Estate (Poplar), which was shown as part of the 1951 Festival of Britain.

Housing built by the LCC was also influenced by the increasingly ambitious nature of its Architect’s Department. Forshaw’s reorganisation and the leadership of chief architect Robert Hogg Matthew from 1946 transformed the department into the world’s largest architect’s office. Controversially, responsibility for designing housing was assigned to the Valuer’s Department from 1945 to 1949, after which it was returned to the Architect’s Department. In 1950 Matthew created a new housing division, first led by H. J. Whitfield Lewis and then by Kenneth Campbell from 1959. They oversaw a group of architects including Colin Lucas, Colin St John Wilson, Oliver Cox, Bill and Gilliam Howell, David Gregory-Jones, Rosemary Stjernstedt, and Edward Hollamby during a particularly fertile period for the department.

From the mid-1950s into the 1960s, these architects experimented with taller buildings and different architectural styles, inspired by ‘soft’ Scandinavian modernism as well as the more muscular modernism of Le Corbusier. Examples of the former include Ackroydon Estate (Wandsworth), where the LCC first trialled tall ‘point’ blocks, and Alton East (Roehampton). Examples of the latter include the Loughborough Road Estate (Brixton), Gascoyne Estate (Hackney), and Alton West (Roehampton), which all feature ‘slab’ blocks of maisonettes.

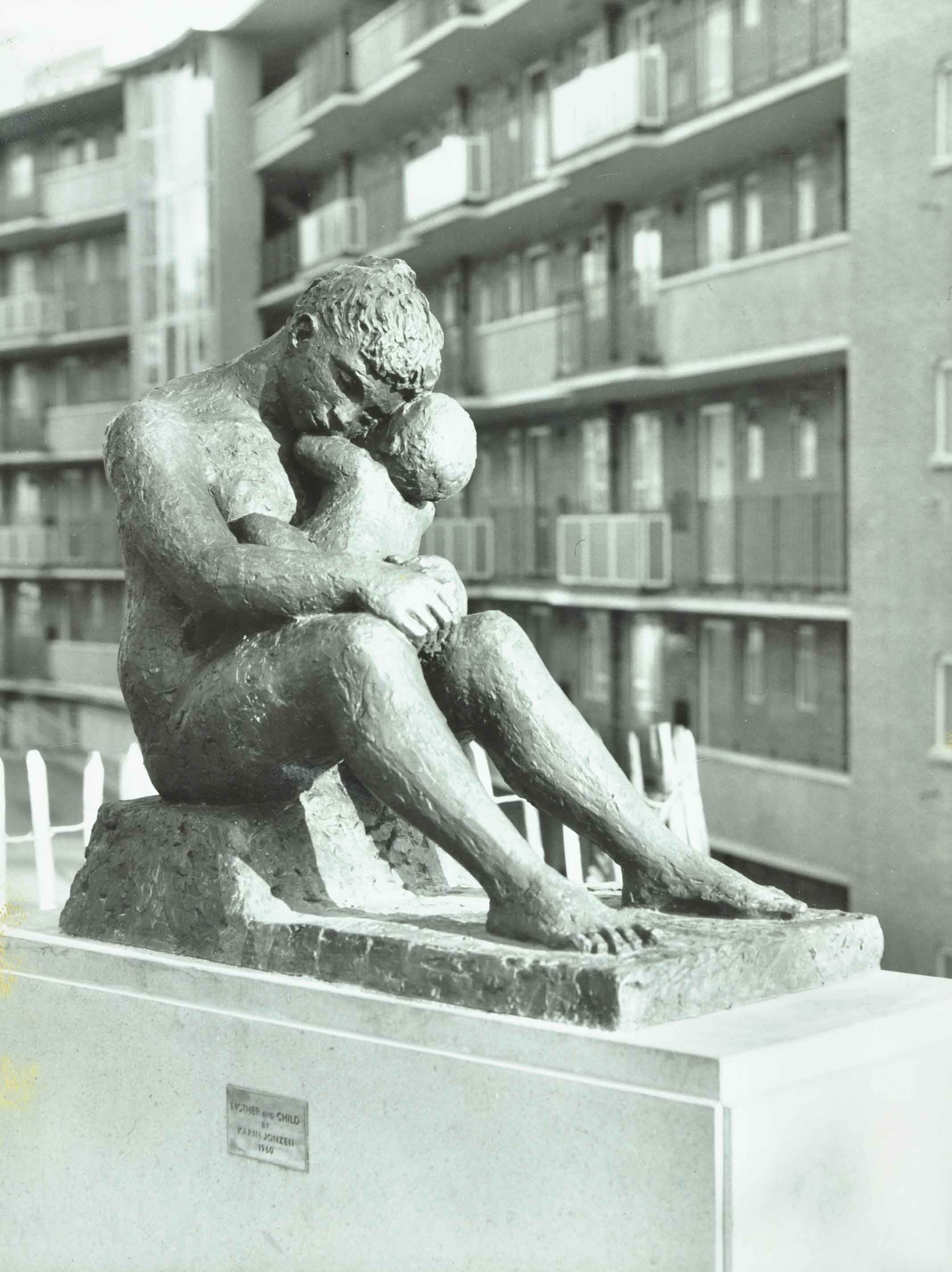

Other estates built during this period include Highbury Quadrant (Islington), St Anne’s Estate (Limehouse), Ashburton Estate (Roehampton), Kersfield, Aboyne Road, and Fitzhugh Estates (Wandsworth) Argyle Estate (Wimbledon), and Sydenham Hill Estate. These estates usually include a mix of low-rise and high-rise blocks and a range of amenities. Some also feature landscaped open spaces, a range of public art funded by the Patronage of the Arts Scheme, and ‘decorative treatment’ by Anthony Hollaway and Lynn Easthope.

In the 1960s, the development of ‘system building’ with pre-cast components meant that it became much quicker to build high-rise blocks, and these became the style of choice during this period. The technical achievements of the 1960s were overshadowed by the Ronan Point disaster of 1968, when a 22-storey tower block in Canning Town, built by Newham Council, partially collapsed only two months after opening. This disaster led to a loss of confidence in high rise social housing amongst the public.

In 1965, the London County Council was abolished and the responsibility for housing was transferred to the newly formed Greater London Council. However, under the London Government Act of 1963 a shift in responsibility for housing to the London Boroughs was in progress. After this transfer, the architectural department of the Greater London Council retained the responsibility for the renovation and restoration of the older estates built by the LCC.

New and Expanding Towns

A feature of post-war town planning, particularly in the South-East of England, was the creation of new towns and the expansion of existing ones to reduce congestion in cities. The LCC was thwarted in its plans to develop a new town at Hook, Hampshire, but it did obtain permission to build housing developments for Londoners in several towns, which the Council called 'expanding towns' and these included Andover, Ashford, Aylesbury, Banbury, Basingstoke, Bletchley, Bury St Edmunds; Huntingdon; Kings Lynn; Letchworth; Luton; Swindon; Thetford and Wellingborough. The Council’s New and Expanding Towns Committee was responsible for these projects, though relevant papers will also be found across the Council’s archives, most notably in the records of the Housing Committee and Architect’s Department.

Other types of housing

There were some other forms of housing built by the LCC with the involvement of the Welfare Committee and Department. These include specialist housing for elderly people (up to 18% of the total accommodation provided by the LCC) including 'flatlets' sometimes integrated into larger developments, sometimes as standalone properties: Lansbury Lodge, Poplar and Eastway Park, Hackney being examples. They built temporary accommodation (known as 'common lodging houses') such as Carrington House, Deptford, which offered short stay accommodation, as well as children’s homes. The LCC also built prefabricated mobile homes in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Research Tips:

- When researching housing estates or developments, please be aware that the names that they were given on completion often differed from the names they were given during construction. You can work backwards through the Council minutes (see Archive Resources below) – or exploit our printed sources on London’s housing – to identify the original name of the estate.

- LMA does not hold all original plans for housing. When responsibility for social housing passed to the London boroughs the plans were often transferred too as they were working documents. These may now be located at local borough record offices, or with the housing associations that run existing developments, if plans survive at all.

- There are very few discrete records regarding individual tenants

- The LCC was not responsible for all social housing in this period: housing was also built and managed by the Corporation of London, London’s boroughs, housing associations such as Peabody and businesses such as the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company

- Material relating to housing transferred to the GLC on the abolition of the LCC – meaning that some material forms part of the GLC archives rather than the LCC archives. So, don’t rule out search results which include files from the GLC collections – check the date that they cover.

Resources

Archive Resources

Many searches should begin with the indexed Council minutes, available to access onsite at LMA in the Information Area. Our introductory guide to the LCC archives should be consulted to understand how to use these minutes in conjunction with the relevant committee minutes and presented papers. The following list identifies the key archival sources for researching housing but is not exhaustive. These are not available online and need to be consulted at LMA:

- LCC/MIN/07236-07801: London County Council: Committees and Sub-Committees: Minutes and Related Papers: Housing

The references above cover the minutes and presented papers of the Housing of the Working Classes Committee (1889-91 and 1896-1920), the Public Health and Housing Committee (1891-96), the Housing Committee (1920-34 and 1947-65) and the Housing and Public Health Committee (1934-47).

- LCC/HSG and LCC/CL/HSG: London County Council: Housing Department and London County Council: Clerks Department: Committees concerned with housing

- LCC/AR/HS/03: London County Council: Architect’s Department: Housing: Estate Plans and LCC/HSG/PP: London County Council: Housing Department: Housing Estate Plans

Architectural records, including block plans, site plans and floor plans as well as elevations, section drawings, and technical drawings can be found in the records of the Architect’s Department and the Housing Department.

- SC/PHL/01 and /02 Special Collections: Photographs

The LCC photograph collection provides a comprehensive visual record of housing built by the LCC, as well as sites marked for slum clearance and estates under construction. The photographs of newly-built estates often capture the holistic vision of the architects, featuring shots of landscaping, artworks, and community halls, as well as exteriors and interiors of flats. Many of these photographs, including all the SC/PHL/01 series, are available to access on the London Picture Archive website.

- LCC/HSG/GEN/02/030-031: London County Council: Housing Department: General ‘Plans for standard types of LCC housing’.

- GLC/AR/PL/14 and GLC/AR/PL/17: Greater London Council: Architect’s Department: Plan Registry, including plans and block plans of various housing estates.

- LCC/PUB/11/01/152-154 and SC/GLC/FLM/147: LCC maps showing housing estates, dated 1928, 1934, 1936, and 1961.

- GLC/DG/PRB/11/015/001: Film 'Changing Face of London' from 1960, focuses on the clearance of bomb-damaged buildings following World War II and the projects and plans to rebuild the capital. The role of the London County Council (LCC), the Architect’s Department, its development plan and planning processes all feature.

Published resources

LMA’s library is the former reference library of the London County Council, which means that we hold a wealth of published material relating to housing, including the numerous publications the LCC produced about their own developments. General histories of the LCC are listed in our introductory guide to the records of the LCC.

- A Revolution in London Housing: LCC Architects and Their Work 1893-1914: Susan Beattie (28.75 BEA)

- Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing: John Boughton (28.76 BOU)

- Intergovernmental Relations and Housing Policy in London 1919-1970 with Special Reference to the Density and Location of Council Housing: L. Garside in London Journal 9:1 (1983). Visitors to LMA can access the London Journal for free using the computers in the Information Area

- Semi-Detached London: Suburban Development, Life and Transport 1900-1939: A. Jackson (40.3 JAC)

- Housing: with particular reference to Post War Housing Schemes (1928): London County Council (28.75 LCC)

- Housing 1928-1930: London County Council (28.75 LCC)

- London Housing (1937): London County Council (28.75 LCC)

- Housing: A Survey of the Post War Housing Work of the London County Council 1945-1949: London County Council (28.75 LCC)

- From the Slums to the Suburbs: Labour Party Policy, the LCC and the Woodberry Down Estate, Stoke Newington: Parker in London Journal 24:2 (1999)

- Ossulston Street: Early LCC Experiments in High Rise Housing 1928-1929: Pepper in London Journal 7:1 (1981)

- The White Hart Lane Estate: An LCC Venture in Suburban Development: Thorne in London Journal 12:1 (1986)

- Ceremonial Pamphlets: 15 volumes of pamphlets published on the opening of LCC developments – such as schools, housing estates, infrastructure projects. Often include considerable detail and photographs. (18.7 LCC)

Periodicals

We hold a range of periodicals relating to architecture and town planning. These include 'The Builder' (35.11, see our research guide 'George Godwin and The Builder' for further details), the 'Journal of the Town Planning Institute' (28.0) and 'Municipal Review' (14.0), 'Architectural Review' (45.0) and the 'Building News & Engineering Journal' (35.11).